About Social Bookmarking

|

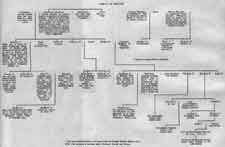

The Procters

of Bordley & Winterburn

At the opening of the sixteenth century, the Procters were a vigorous race in Craven. At various houses in the township of Bordley, in the parish of Burnsall and at Winterburn, Friarshead and Cowpercote, in the parish of Gargrave, were established substantial families of the name, all tenants of Monastic Houses. It was a common practice of these establishments to lease the more remote portions of their landed property for terms of years at fixed rentals. By renewal of leases such properties were often held by successive generations of one family, a continuity of possession which conferred a measure of territorial importance. Of such a family, Geoffrey Procter of Bordley, a tenant of the Abbey of Fountains, was the representative. He died in the second half of 1523 or early in the following year, and his long and very interesting will proves him to have possessed a very considerable estate both in lands and goods. In a deed of the twenty-sixth year of Henry VIII (Calton Deeds, 56), he is described as 'Geoffrey Procter auditor deceased', and from a petition to the monarch last mentioned ("Yorks. Record Series XIV, p152 - Star Chamber Proceedings), it appears that he was 'auditor' to Henry, Earl of Northumberland, a position which was perhaps analogous to that of the agent of to-day. By his will dated 'at Nether Bordley in Craven the tend daye of Jany' in the sixteenth year of Henry VIII -1524 (Printed in Test. Ebor, V, 182. Surtees Soc. Vol 79), Geoffrey directs that in case he shall die within twenty miles of his parish church of Rilston, he shall be there buried with his wife. He proceeds to charge his lands in Litton, Owlcoottes, Hawkeswike and Scothorp in Craven,

In 1597, John Procter, who was possibly a younger son of Richard Procter of Bordley, was owner of the estate. He died on 24 November of that year, and Livery of his lands was granted to his son and heir, Thomas, in the forty-second year of the same reign (Pocter deeds). The grant shows that John held in chief by the service of the hundredth part of a knight's fee, the capital messuage called Bordley Hall, in Nether Bordley, ten messuages, ten gardens, ten orchards, one water corn-mill, two hundred acres of arable land, one hundred acres of meadow, two hundred acres of pasture, two hundred acres of moor, two hundred acres of turbary, and three hundred acres of gorse and heather, with all appurtenances of the said manor or capital messuage in Over Bordley, Nether Bordley, Kirkby, Burnsall and Malham; also the advowson of the Vicarage of Gargrave and three messuages with ten bovates of land belonging to them in the same vill. The Bordley property is valued by the year at £63 6s 8d and that in Gargrave at £2 135. 4d. Bordley Hall, which by tradition is reputed to have had seven outer doors, has been replaced by a modern farmhouse built in 1749 and no trace of its chapel remains, save the name, Chapel-garth, which appertains to a field adjoining the house on the west. (References to the Chapel occur in the Parish Register of Rilston, for example the following: 1671, Ed. Hebden and Isabel Ayrton married at Bordley Chapel') With the exception of a small portion which was sold to the Leeds and Liverpool Canal Company, the Procters still own the estate. A contemporary of Geoffrey of Bordley was Thomas Procter of Friar's Head in the township of Winterburn, which he held of the Abbey of Furness. His will, dated on 22 May 1507, directs that he shall be buried in the Church of St. Andrew, of Gargrave, and expresses a hope that the post which he holds under Furness may be bestowed by the Abbot on his son, Stephen. To his wife, Eden, and his said son Stephen, he gives his farm of Friar's Head —'volo quod Eden uxor mea et Stephanus films meus habeant firmarium meum de Frerehead.' (Test. Ebor, Vol. V. p. 182 note. Surlees Sot.)

Another contemporary was Ralph Procter, who, by his will, dated on Easter Day 1512, like the others, desires burial in the Church of St. Andrew, of Gargrave, near the grave of his father, 'ex austral!parte prope sepulcrum patris mei'. As executors he appoints his grandfather Roger Prokter and Sir John Acastre, Vicar of Gargrave ( Test. Ebor, Vol. V. p. 182. Surtees Soc.). In the absence of direct evidence of the fact it may probably be taken for granted that the Procters of Bordley and those of the adjoining township, Winterburn, were of the same stock. In Winterburn, Flasby, Hetton, Eshton and Airton, the Monastery of Furness had extensive possessions of which some details are furnished by a Rental preserved in the Treasury of the Exchequer at the Chapter House, Westminster, and made for the last Abbot, as under :

On the death of Abbot Banks, shortly before the Dissolution,

a certain monk, by name, Hugh Browne, having possessed himself of the

Convent's Seal, affixed its impression to a number of blank sheets of

parchment which in return for a suitable consideration he handed to

various individuals. That the Earl's lease was written on one of these

sheets without the knowledge or consent of the convent, Procter and

his friends succeeded in convincing the Commissioners, since a decree

restraining the Earl was issued. New leases were granted to Procter

and his associates and he was reappointed to his old office of bailiff

and receiver of the Abbey's lands now vested in the Crown. In the days

of Edward it was not an easy task to enforce an order upon a powerful

noble whose stronghold lay in the wilds of Craven; the decree was ignored

by the Earl, and Procter, unable to get possession of his lands, in

the year 1556-7 again petitioned the Crown for redress. At this period

the operation of the law was not only costly but slow. The suit had

lasted twenty-one years and had entailed heavy expense, which coupled

with his inability to derive any benefit from the occupancy of his manor

and land, had seriously crippled Procter's resources. He pleads that:

In this same year a letter from Thos. Windebank to Walsingham refers to Thomas Procter's negotiations with the Emperor of Russia, while in the following year Edward Anlabye complains of the loss occasioned to him 'by reason of the same privilege'. (Cal. State Papers) A further echo is found in the record of a Chancery suit by Sir Edward Fytton v Stephen Procter et al. 'For account respecting partnership —an undertaking for the working of iron with sea-coal and turf, in pursuance of the queen's letters-patent granted to Thomas Procter, esquire, and another, in which plaintiff was to have a concern'. It certainly seems a plausible hypothesis that Stephen derived some of his wealth from this early smelting undertaking, which, on the death of his father had evidently passed into his hands. By 1596, at any rate, he was enabled to purchase the extensive estate of Fountains and the following year he was made a Justice of the Peace for the West Riding. The acquisition of Fountains immediately involved Stephen

in a series of lawsuits and gained for him the enmity of powerful neighbours,

the Mallorys, who were to be a thorn in his flesh till the end of his

days. In 1602 he was charged with making slanderous speeches against

the Earl of Derby and brought a countercharge of riot in the Court of

Star Chamber against the Earl's officers. In a letter to Cecil, John

Mallory writes: Some years later equally violent proceedings became the subject of a suit he brought against Darnbrook and others in connection with 'one horrible riot' committed at his lead mines. From these first legal frays Stephen appears to have emerged unscathed; in fact they seem to have whetted his appetite for litigation. Shortly after the accession of James I he was knighted at the Tower —on 14 March 1604. The following year, on 1 November, he was admitted to Gray's Inn. His affairs prospered and he proceeded with the erection of a fine new house, Fountains Hall, built with stone from the Abbey hard by: the house, a fine Renascence structure, its front ornamented with figures of the Nine Worthies, was completed at a cost of £3, 000 in 1611. Whatever his personal convictions may have been, he certainly turned the prevailing religious situation to account, and having procured appointment (31 July 1609) as 'Collector and Receiver of Fines on Penal Statutes' (Cal. of State Papers, James I) zealously hunted out recusants, harbourers of seminaries, and all in the least degree suspect in matters of religion. Such excessive zeal was to prove his undoing, quite apart from any question as to the proper partition of the sums collected. Already in 1602 he had exhibited in the Star Chamber a bill against Sir William Mallory alleging that by his 'countenance and remissness, the county hereabouts had relapsed into disobedience in religion'. In February 1609, William Falconbridge writes a memorandum of the practice of Sir Stephen Procter, Lady Procter and others against Sir John Mallory (Cal. of State Papers, James I), while on 21 August of the same year, Procter complains to the Earl of Exeter of injuries done to him by Sir John Mallory (Cal. of State Papers, James I). Within twelve months of his installation in his new office, Stephen was accused of 'vexatious abuses in the exercise of his patents' (Cal. of State Papers, James I). He had reached the climax of his success and his fall was not long to be delayed. Soon he was proceeded against in the Star Chamber on a charge of 'scandal and conspiracy' in 'endeavouring unjustly to involve two Yorkshire Knights in trouble about the Powder Plot and for slandering the Lord Privy Seal' (Cal. of State Papers, James I). Though he was found guilty and sentenced to imprisonment and the pillory, and to pay a fine of £3,000, he was acquitted on appeal, the panel of judges being equally divided (Coke's Institutes). Nevertheless, his ruin was now accomplished and we hear of him no more. In 1619 there was some talk of renewing on behalf of another, 'with certain exceptions and provisoes', the office formerly enjoyed by Stephen, now apparently living in retirement. His death must have occurred somewhere about this time, but no record of his burial-place has been discovered, though his arms are to be seen in a window of the south aisle of Ripon Cathedral. Administration of his estate was granted on 24 April 1620 to his widow, who, together with four daughters, co-heiresses, survived him. Julie Anne, daughter, and Lacie, son, of Stephen Procter gentleman, who were buried at Gargrave in 1614 and 1618 respectively, were probably the children of a relative and not of Sir Stephen. His brother Elias died in 1621 and his widow Honor in 1626. Shortly after his death, the Fountains estate was conveyed by his widow and three of his daughters and co-heirs and their husbands, viz. Thos. Jackson of Cowling and Debora his wife, George Dawson of Azerley and Priscilla his wife and Stephen Pudsey of Arnforth and Beatrice his wife, to Sir Timothy Whittingham, for £3,595. On 15 October 1625, Sir Timothy, with Thomas Procter and others, conveyed the property to Humphrey Wharton for £3,500. Finally, on 27 May 1627, Humphrey Wharton and Thomas his son, with Broythwell Lloyd and Honora his wife, another of the co-heirs of Sir Stephen, conveyed the property to Richard Ewens and his heirs for £4,000, his son-in-law John Messenger advancing £2,700 of this sum. Exactly what this curious series of transactions implies it is difficult to say: probably these transfers were to some extent fictitious, but it is certain that with the last of them, the Fountains estate passed from Sir Stephen's heirs for ever. The central window of the great chamber of Fountains Hall contains a fine display of heraldic glass which dates from Sir Stephen's time. Over fifty shields of impaled arms purport to record alliances of the Procters, and of a number of other families with which it is generally believed the Procters had no connection. Beneath each shield appear the surnames of husband and wife and occasionally the Christian names of their children. It will be noticed that prominence is given to the family of Mirewray, and that in four instances members of that family are described as Mirewray alias Procter, while in the record of Stephen's own marriage, he is described as 'Stephen Procter alias Mirewraye. 'Moreover the same shield of arms, viz. argent, a chevron gules between ten crosses crosslet sable, six in chief and four in base, is given as the arms of both these families, though there is certainly no record of any grant of arms to Sir Stephen, or to any of his immediate ancestors. Who were these Mirewrays? The name is clearly a northern name, a compound of 'rnire '= marshy or boggy land, and 'wra '=corner, angular piece of land. It is much the same as Mirfield, and characteristic of the Cumberland —E. Lancashire — W. Riding area. Thus it is not surprising that we should come across this family in the neighbourhood of Bentham and Clapham. The earliest record we have discovered relates to the year 1231 when Adam de Mirewrae was a witness to an undertaking by Gregory de Burton to pay the monks of Furness four shillings a year (Furness Abbey Coucher Book. Vol. II, part 2, p. 481), while the following is a complete list of all the occurrences of this name we have so far been able to trace:—

The last of these is taken from the Poll Tax Return of 2 Richard II, under Bentham, and the others are all associated with this district, and with families of distinction such as the Tunstalls, Hornbys, Claphams etc. Now, how can this family, which disappears from history before the end of the fourteenth century, have any connection with the Procters? There are two possible explanations. Either a Procter married an heiress of the de Mirewras, or a de Mirewra younger son, holding an appointment as procter for the monks of Furness, in course of time adopted his title as his surname. It is significant that the name 'Procter 'did not exist as a surname in this neighbourhood until the Abbeys obtained license to lease their properties to tenants and so had to appoint procters to represent them in the Courts: this, in most cases, occurred about 1350. In the earliest lists of tenants, the surname Procter occurs frequently, and it has been widespread in the Bentham, Newby and Clapham districts ever since. Whatever the truth may be, it is evident that this is the family from which Sir Stephen believed, or wished it to be believed, that he was descended. But had this family the right to bear arms? The coat in question is given in Papworth and Morant's British Armorials as the arms of Malemayne, Malmaynes, Mereworth or Merworth, William M'Wire but Merwre Harl. MS 6137. The last of these bears such a strong resemblance to Mirewra that it is hardly an unfair assumption to regard it as merely another variant, and since Harl. 6137 refers to the Acre Roll of 1192, perhaps the earliest. So despite John Mallory's acid, 'he forgets what he has been', Stephen could reflect with pride that four hundred years before, his crusading ancestor had fought nobly under Richard Coeur-de-Lion. Again, the third of these names supplies the clue to another of the problems presented by the window at Fountains, in which Sir Oliver Mirewraye is described as 'of Tymbridge in the Countie of Kent', for the Mereworths were of Mereworth Castle, about six miles N. E. of Tonbridge. Stephen clearly intended to make assurance of his noble lineage doubly sure, and so adopted the Mereworths as an offshoot of the de Mirewras. With patience, quite a number of the alliances recorded in the window can be traced, particularly the more recent ones such as that of Thomas Procter and Grace, daughter and heiress of Thomas Nowell of Read who died in 1575. The most recent would appear to be Derbye-Oxenford, referring to the marriage in 1595 of Wm. Stanley, sixth Earl of Derby, the nobleman he was alleged to have slandered, and Elizabeth de Vere, daughter of the 17th Earl of Oxford. How Stephen can have been connected with either of these families cannot easily be conceived. Perhaps the whole record was the work of a complaisant herald, and worthy to be compared with that of Dethick and Camden in the contemporaneous case of William Shakspere. It is at least amusing to find a Mirewraye-Mallory alliance included. Read the complete will of Geoffrey Procter of Bordley. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|