A rose motif, was it for the House of York or Lancaster?

The Tudor Rose

A rose motif, was it for the House of York or Lancaster?

If you examine the bosses on the roof beams in St Michael's church, you will not only see the unusual face hiding the rood pulley, but also some carved roses, one has a single row of petals and another a double row.

The origins of the rose emblem are said to go back to Edmund of Langley (1341-1402), the first Duke of York and the founder of the House of York.

The symbolism behind the rose has religious connotations as it represents the Virgin Mary, who was often called the Mystical Rose of Heaven.

The Yorkist rose is white in colour, because in Christian liturgical symbolism, white is the symbol of light, typifying innocence and purity, joy and glory.

The Tudor Rose.

During the Wars of the Roses between the Houses of York and Lancaster in the fifteenth century, the Red Rose was the symbol of the House of Lancaster.

The conflict was ended in 1485 and King Henry VII (1457-1509) of the House of Lancaster (Red Rose) married Elizabeth of York and symbolically united the White and Red Roses to create the Tudor Rose, symbol of the Tudor dynasty.

The single petal rose doesn't have any paint remaining, so may have shown support for either the House of York or Lancaster, but the double petal Tudor Rose does tend to confirm the period when this church and roof were thought to be built at the end of the 15th century.

The lost wall paintings

A glimpse of medieval wall painting under many layers of whitewash.

Entering St Michael's church today, you are struck by the simplicity of the decor, but if you had been a medieval visitor you would have seen seen a much more colourful interior. There were wall paintings and features such as the roof beams and bosses were picked out in colour. We know this because of written comments and a few traces which were left behind and discovered during recent renovations.

Very few English churches managed to keep their wall paintings through the period of the English Reformation. There are one or two notable examples and there are probably some others, still to be discovered underneath layers of whitewash and plaster.

The medieval wall painting in Kirkby Malham church was painted over and unfortunately the remains of all the wall paintings at Kirkby Malham were chipped off by the Victorians when the church was restored in 1880. Only a few minute traces were found when the Victorian plaster was replaced in 2005, hinting at what might have been.

Wall paintings in local churches would have used a fairly restricted pallette, earth pigments red and yellow ochre, together with black and white, variously mixed to provide a surprisingly wide range of shades, would form the basic palette. Blues, greens and expensive gold leaf were much more rare outside of cathedrals and minsters.

However we do know from various accounts that Kirkby Malham church had several phases of wall painting. The earlier medieval decorations were painted over, then post-reformation wall paintings were added, and these usually took the form of religious texts in other churches.

The remains of a post-reformation text.

What appears to be a later phase of painting at Kirkby Malham was still to be seen when the Victorian restoration was undertaken in 1880, and earlier in the century TD Whitaker in his History of Craven wrote: -

"on the north side of the tower-arch is the remains of a wall painting of a skeleton, with the words Momento Mori, in black letter over it, and on the south side an angel holding an hour-glass."

Thomas Brayshaw in an article written for the Craven Herald in 1924 says :

"On the west wall there were quaint frecoes representing "Time" and "Death", and when these were scaled off texts in black appeared. Beneath this coating there were illuminations in red, and deeper still were other designs."

This was written long after the Victorian restoration, but Thomas Brayshaw was married in the church tower at the time of the church restoration, whilst the roof was being renewed. From the few scraps of painted plaster remaining on the north wall when the plaster was replaced in 2005 we can certainly see evidence of at least two phases of this wall decoration.

Paint remaining on roof beam.

Medieval wall paintings were not the only decoration that would have been seen, roof timbers and ceilings were often painted too and remains of colour can still be seen on some roof timbers at Kirkby Malham. Other churches are more fortunate and still have larger examples of mediaeval decoration, such as this portion of a chancel screen in a Norfolk church.

St Helen's Well, Eshton

St Helen's Well, Winterburn Lane, Eshton. © Copyright Humphrey Bolton

The well lies beside the road from Eshton to Winterburn near Nappa Bridge (Map Reference SD9309 5701). It is surrounded by a dry stone wall on the road side and an iron railing at the back which encloses a wooded hollow with a pool about 4 yards across. The fresh water bubbles up towards the back of this pool. Prior to 2004 the outfall from the pool was in the form of a curved masonry weir or curb, its ends terminating in squat square carved pinnacles in gothic style. Spaced equally along the length of the curb were three semicircular projections extending into the pool, each projection having a vertical hole in the centre. At first sight these just looked like buttresses overgrown with moss and weed, but if one felt underwater, they were carved in the form of human heads permanently submerged. This ancient well was reputed never to run dry but in the summer of 1996 it did dry out and there was the opportunity to photograph the faces on the stone heads which were normally under water.

One of the stone heads at St Helen's Well, stolen in 2004.

In April 2004 the heads were stolen and although photographs taken in 1996 were circulated by the police and one was published in the Craven Herald, their whereabouts has not come to light. The curb was rebuilt by the farmer whose land adjoins the well but the old heads are no doubt now decorating someone’s garden or building! How sad that such an historic place has been vandalised.

There appears to be no definitive record of where these stone heads came from, but one school of thought is that they were removed from Gargrave Church when it was restored and that the stones may have been obtained by Sir Mathew Wilson and used on the well which lay on his estate. However Harry Gill in his book ‘The Ecclesiastical Parish of Gargrave, Volume 2’ says ‘The pinnacles are those placed on the tower of Gargrave Church at its restoration in 1853, and were blown down on Christmas Eve some two years afterwards. Some stonework fell on the roof, and damaged the font. These were begged by the owner of the Well, and he carted them where they are now’. There is obviously a discrepancy between these two versions so which is correct, if either, is open to debate; but the heads are certainly not of Celtic style and it is thought that the pinnacles are more likely to be late 18th century or early 19th century rather than more ancient.

The association of wells and springs with mysticism and powers of healing goes back to pagan times and the legends surrounding them are often a mixture of pagan, Norse, Celtic and Christian beliefs. Any life giving water which emerged from the earth and never froze in the coldest winter or dried up in the hottest summer has, during the centuries, been thought to have mystical and curative powers.

The earliest history and true age of St Helen’s Well is shrouded in mystery. The well was associated with a Chapel of Ease in medieval times. The first known reference is that in 1429 a commission relating to the manor of Flasby sat ‘In capella beate Elena de Essheton’. It is thought that the chapel was in the field opposite the well, still called Chapel Field. But the name St Helens means that the well could go back much further in history to beyond the Roman Empire to pre Christian times. Constantine, the first Christian Emperor, (306 – 337 AD) was the son of Constantius and Helena who was a Christian and later beatified. Constantine ruled from Eboracum or York and his mother became a favourite Yorkshire saint who gave her name to many holy wells and springs when they were re-dedicated to Christian saints after the coming of Christianity.

St Helen's Well before the carvings were stolen in 2004.

How the well was used through the centuries is not known but in his book ‘The Legendary Lore of the Holy Wells of England’ written in 1893, R C Hope wrote ‘It was customary for the younger folk to assemble and drink the water of this well mixed with sugar on Sunday evenings. The ceremony appears now to have died out. It was in vogue late in the last century’. Certainly for the last twenty years candles and flowers have been placed around the well and ribbons tied in the trees. This still continues, so despite the loss of the stone heads the well remains a significant place for some people.

Rosemary Bundy

Bibliography:

Whitaker - ‘History of Craven’

Harry Gill - ‘Ecclesiastical Parish of Gargrave, Vol 2’

Edna Whelan and Ian Taylor - ‘Yorkshire Holy Wells and Sacred Springs’

Peter Brears - ‘North Country Folk Art’

RC Hope - 'The Legendary Lore of the Holy Wells of England', 1893.

"Lost" 18thC signpost

The signpost and the gateway it now forms part of, on the road to Airton.

Driving through Malhamdale you may well have missed this 18th century signpost which is now doing duty as a gate post. The first edition 6 inch OS map shows that in the 1850s it still stood near Newfield Bridge, opposite the telephone exchange, where the road turns off to Coniston Cold. It was probably moved in the war, when all road signs were taken down to fool enemy invaders who had forgotten to bring a map with them. Unfortunately the place names have been defaced, probably at the same time, however you can still see the hand pointing into the field as you approach the Coniston Cold turning from Airton (Map ref. SD9055 5812).

Rood Screen Pulley

The rood pulley showing rope holes and original paint.

When your eyes stray to the roof beams in the Parish Church you may have seen a carved wooden face looking back at you. This likeness has been gazing down on congregations for around 500 years and is not as you might think, a purely decorative feature, but a very functional one. It houses a pulley for a rope, which would have passed up through the hole in the mouth and down through the hole in the chin, and although fragile, it is still working after all this time.

It is thought to be associated with the Rood Screen (also choir screen or chancel screen) which was a common feature in late medieval church architecture, dividing the chancel (the area with the main altar in a church) from the nave (the main part of the church for the congregation), but few survived the Reformation. Typically it consisted of an ornate screen which was surmounted by structure called a rood loft or beam carrying the Great Rood, a sculptural representation of the Crucifixion. The word rood is derived from the Saxon word rood or rode, meaning "cross". The rood provided a focus for worship, especially in Holy Week, and during Lent the rood figures were veiled, being revealed on Palm Sunday.

Rear view showing the pulley and the peg attaching it to the roof beam.

It is assumed that the reason for our pulley was to raise or lower this cover over the Great Rood, a function it would still be capable of today, if there was one. The head is a fine piece of medieval woodwork, though perhaps "cleaned up" by the Victorians, and is held in position on the roof beam by a mortice and tenon joint and a wooden peg, and the small amount of colour on the lips shows that it was once painted.

View showing the wooden axle for the pulley.

The Vicar’s Report, dated August 1924, contains an anecdote relating to the carved head on the pulley from the time when Rev Henley was the incumbent (1871-1898). For several weeks the Rev Henley had been disturbed because of the lack of concentration and restlessness of the congregation. Instead of attending to the service and listening to the sermons the congregation were shifting in their pews and constantly glancing at the carved head on the roof beam. Rev Henley eventually spoke to the sexton to see if he could throw any light on this unusual behaviour. He was told that the congregation were concerned because the face could regularly be seen putting its tongue out. Needless to say the vicar was adamant that such a thing was impossible but the sexton was not convinced by this answer and continued to protest that he had seen it several times himself. Eventually, to prove that this was not possible, the vicar had ladders brought and the face was carefully examined. It came to light that a spider had spun a loose web across the open mouth of the face and the draught made it wave backwards and forwards. As the light caught the web it had all the appearance of a tongue being stuck out. Problem solved!

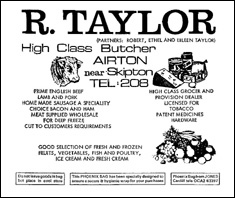

Malhamdale Businesses

The Victoria Hotel

Some members of the Local History Group are undertaking a project to look at the range of non-agricultural businesses and trades that have been undertaken in the Dale over the years.

J Carradice, Grocer, Airton

Today there are only a few shops and business premises left offering a limited selection of goods and services, but in the past there has been a great variety, varying in size from cotton mills to handloom weavers and individuals making straw hats and skewers.

The last shop in Airton

The History Group would be very pleased to hear from anyone who has information about individual businesses or who have any photographs, old bills, advertisements or similar ephemera depicting Malhamdale businesses or business people.

Scalegill Cotton Mill